The 6th Airborne Division

Accueil » The Museum » The Battery » The 6th Airborne Division

The 6th

airborne division

In June 1940, Winston Churchill wanted Britain to have an airborne force. As a result, at the Winston Churchill’s instigation, the first parachute school, The Central Landing School, was set up at Ringway Air Base near Manchester.

It was commanded by a Major from the Royal Engineers.

At the end of 1941, Major General Browning was appointed to command the 1st Parachute Brigade.

To him is credited the famous maroon beret and the legendary Pegasus horse as emblems of the airborne troops.

The 1st Parachute Brigade was under the authority of Brigadier Richard N. Gale.

It included the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Parachute Battalion. In the summer of 1942, Brigadier Richard N. Gale joined the War Office and became a Major General. At this time we find Lieutenant-Colonel James Hill in command of the 1st Parachute Brigade with Major Alastair Pearson as his assistant. The Second in Command was Major Pine-Coffin. All these officers were to participate in the 6th Airborne’s Great Leap into Normandy on the night of 5-6 June 1944.

At the beginning of 1942, the German High Command was impressed by the success of the airborne assault on the Bruneval radar station, near Le Havre.

In Summer 1942, the Parachute Regiment is formed. A second brigade, with three battalions, was set up. The direction was given, and an Airborne Division was waiting to be born. This would happen at the end of the Sicily engagement, which followed the North Africa engagement.

In the first quarter, the 1st Airborne Division was developed following the wish of the War Office, which decided on the formation of a new Division, named the 6th Airborne Division.

It was entrusted to Major General Richard N. Gale, who, in keeping with his forceful personality, set up a training programme to make his Division an elite unit. In mid-1943, the 6th Airborne Division lined up its three Brigades. Canadian paratroopers came to reinforce the ranks of the 6th Airborne Division.

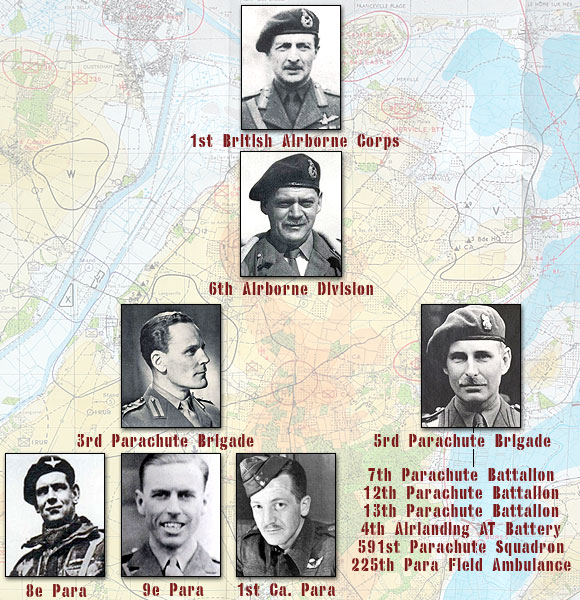

By this date, the organisation chart presented above had been developed, with the High Command and the 6th Airborne Division with the 3rd Parachute Brigade under Brigadier James Hill and the 5th Parachute Brigade under Brigadier Nigel Poett.

The 6th Airlanding Brigade (not shown on the organisation chart) must also be included.

In the summer of 1943, Brigadier James Hill, in command of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, thus commanded the 8th Parachute Battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel Alastair Pearson, the 9th Parachute Battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel Terence Otway, and the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion under Lieutenant-Colonel George Bradbrooke.

From top to bottom and from left to right.

Major-General Browning.

Major-General Richard N. Gale.

Brigadier James Hill and Brigadier Nigel Poett.

Lieutenant-Colonel Alastair Pearson, Lieutenant-Colonel Terence Otway and Lieutenant-Colonel George Bradbrooke.

The 3rd Parachute Brigade

Brigadier James Hill commanded three parachute battalions, including the 9th. Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway commanded the 9th Parachute Battalion.

A Parachute Battalion consisted of approximately 750 men.

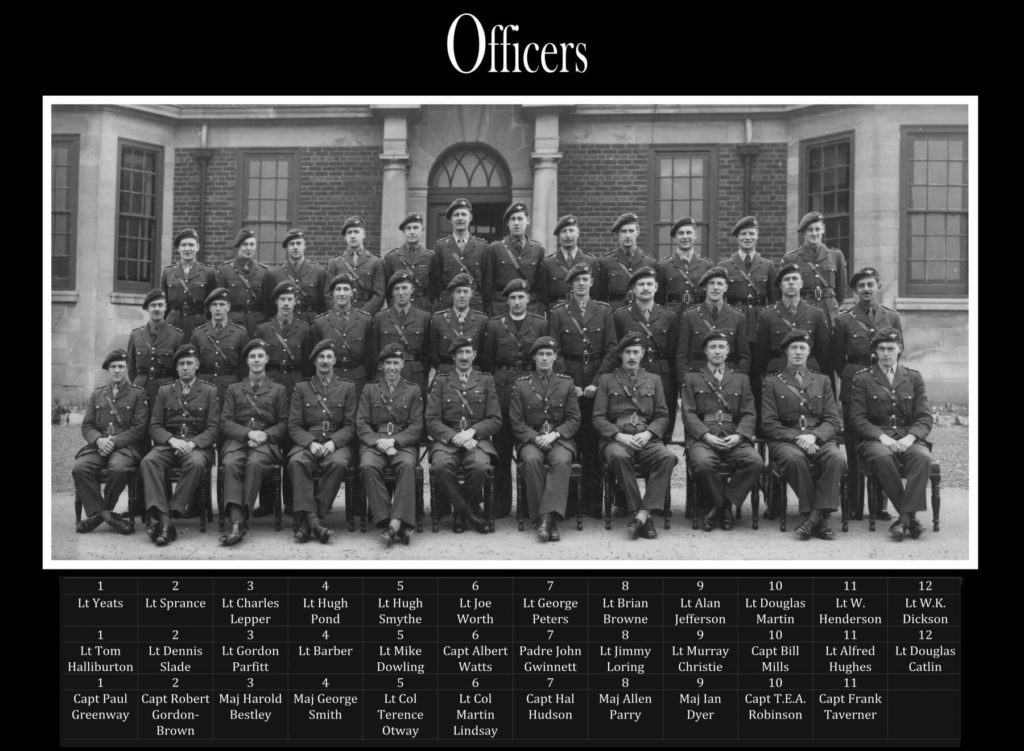

The 9th Battalion had its Headquarters and a Command Company. Opposite, we see Lieutenant Colonel Terence Otway with all his officers.

Like every other, the 9th Battalion had three parachute companies (5 officers and 120 men per company) named A, B and C, each with 3 sections.

The elementary group consisted of eight men plus a sergeant and a corporal.

This group is also known as a “stick” (a term recalling the rosary shape formed by the men when jumping off the transport quickly one after the other). The Dakotas carried 2 sticks with their containers.

Not to be forgotten in the 9th Battalion were the scouts, signals, intelligence, airborne glider infantry, sappers and medics, and two sections with Vickers machine guns and 3-inch mortars.

Units of the 6th Airborne Division

In 1944, the 6th Airborne Division consisted of:

The 3rd Parachute Brigade and its 3 battalions;

The 5th Parachute Brigade and its 3 battalions;

The 6th Airlanding Brigade transported by gliders;

The 6th Airborne Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment;

The artillery;

The Engineers;

Communications; The Medical Corps;

The Transport Service;

Air Transport.

Land at Hardwick Hall; Air at Ringway

The training camps of the 6th Airborne Division

The first contact with the airborne troops was made at Hardwick Hall, near Chesterfield. The men would spend a fortnight there. This first period principally involved a decisive test of both physical and mental abilities. And even though the training was intensive, tough and more rigorous than in traditional centres, it was nothing compared to what awaited the volunteers for the airborne troops later on.

Once land training was completed (the Airborne Corps is controlled by the Army and the Royal Air Force), air training would begin at Ringway Air Base near Manchester. The objective: the drop. Each parachutist had to make two jumps from a balloon and six from an aircraft. The maroon beret and Pegasus crest could only be earned after the first jump from a balloon.

First jump: from a tethered balloon. Height: about 250 metres. Deathly silent and terrifyingly cold blooded. Free fall before (hoped-for) canopy opening : 40 metres. Effect: the whole body weight drops suddenly, and straight down. Then came the jumps from the twin-engine Whitley aircraft: everyone had to jump through a deep hole in the middle of the floor of the bomber, carrying more than their own weight in equipment ! It is no mean feat (and adds to the ordeal of the jump itself) to launch oneself without smashing against the edges of the opening. Again, the training was tough and intensive.

Then, at the end of this training, came the Wings Day, the day the men had so much been waiting for. It was the day that would leave everyone with a memory for life. This day is the day of consecration, the day on which the insignia was awarded.

This day is especially important, as by agreeing to receive his wings, each parachutist solemnly committed himself never to fail to fly or jump. A real oath was made on Wings Day.

From that day on, the paratroopers, adorned with all their awards, were allocated to their respective battalions. But they were still far from imagining, despite what they had just experienced, what awaited them to complete the training.

Bulford training camp

These men, of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, would now be trained by Brigadier James Hill at Bulford Camp. As will be see later, this Camp is not far from the site chosen by Lieutenant Colonel Otway to implement the specific training of the 9th Battalion.

Brigadier James Hill’s main objective was to bring his men to the best of themselves, the best of their abilities. He knew well, after being seriously wounded in North Africa, that paratroopers in the field are poorly armed and can only rely on their own resources to survive and fulfil their objectives. To this end, he developed a shock training programme to turn his troops into elite men capable of surpassing the common limits of endurance. And we will also see that if Brigadier James Hill had not demanded from his Brigade and in particular the men of Lieutenant Colonel Otway’s 9th Battalion what he required of them, history might not have been written in the same way.

Armed with his experience, Brigadier James Hill was to tell many officers and sub-officers as they departed: “Gentlemen, despite the excellence of your orders and training, do not be intimidated if chaos reigns. Rest assured, reign it will.”

But for now, back to his training programme. Brigadier James Hill’s nickname was ‘Speedy’. And speed was effectively the thread that ran right through his programme. For him, the parachutist in the field must not only go fast, but very much faster than normal. As we have said, endurance was a major component of his training. Brigadier James Hill was relentless in his quest to make the right move as quickly as possible to preserve the paratrooper’s life and lead him to success in his mission.

The training was very hard, very testing, and extraordinarily severe. Brigadier James Hill could be found leading 25km cross country races, and leading them with a vengeance. He was always in front and led valiantly by example.

In addition, he aimed at the excellence of each parachutist in his speciality. And here again, nothing was withheld from the men of the 3rd Parachute Brigade. The different techniques demanded by in combat were repeated day and night. Here too, Brigadier James Hill was well aware that his men, despite being isolated behind enemy lines, would have to face the darkness of night. They would only have a chance of survival if they could fight against the darkness as well.

And every man knew it. Brigadier James Hill would consider his men ready for the Big Jump when they were able to travel about 200 kilometres in just three days with all their kit, about 35 kg of it, on their backs.

Even in the midst of total chaos, the paratrooper for Brigadier James Hill must never admit defeat. He would therefore constantly seek for his men to forge the strength they would need to combat the chaos, for no one in those Dantean moments would be able to help them. All they could rely on was their stamina and their strength to fight for days on end, with little sleep and sometimes with hand-to-hand combat. The enemy had more men than they did, and subjected them to heavy fire, shells and mortars..

But they had been tried and tested, in order to survive and overcome.

Bulford, on Salisbury Plain, in Wiltshire.